Research Article

Identifying the Congregation’s Corporate Personality

Michael C. Rehak

Journal of Psychological Type

Volume 44

1998

Identifying the Congregation’s

Corporate Personality

Dr. Michael C. Rehak

Pastor - Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

Most congregations appear to

know clearly and emphatically

who and what they are not.

Few know who they are.

Applying type theory in corporate or

group settings can bring healing and grace.

Abstract

The MBTI (Form G) was administered to 127 participants; 76 active, adult member of Redeemer Lutheran Church and 51 former members classified as “inactive.” This congregation demonstrated a definite preference for I, N, and F. An inventory for corporate personality that was developed and administered to a select group, further disclosed a preference for P. The group of inactives showed levels of significance for E, S, and J, with a preference for F. Of those who became inactive, 51% preferred the feeling function with the extraverted attitude and another 25.5% extraverted the thinking function. This is in contrast to the INFP corporate personality of this congregation, which holds its judging function of feeling introversively and extraverts the intuition. The research reported here is obviously limited because the study sample is only one congregation, but the results and implications invite further research and dialogue.

Congregations, as other corporations, have personalities. Walter Wink is one of the few who has considered congregations as having corporate personalities. In his book Unmasking The Powers (Wink,1986) he suggested that congregations have personalities which are given at inception and rarely change throughout the life of the congregation. Wink addressed the relative health of congregations in spiritual and theological terms, but made no attempt to identify types. In the secular world, corporate personalities have been theorized and described by William Bridges in his work The Character of Organizations (Bridges, 1992). Bridges identified and described 16 corporate personalities in the language of the MBTI.

Numerous studies and supportive materials for understanding and working with type in organizations, including churches, have been produced. Implications of Communication Style Research for Psychological Type Theory (Yeakley,1983) considered the communication style by type for the pastors and the change that may bring to a congregation’s membership. God’s Gifted People ( Harbaugh,1988) utilizes type theory was written to help parishioners better understand and embrace their unique gifts. Personality Type and Religious Leadership (Oswald and Kroeger, 1988) focused on the pastor as leader. Isachsen and Berens (1988) and Hirsh and Kummerow (1987) are are among those who have published important material for applying type theory in the corporate world. These supportive studies and materials have addressed type issues as individualistic on the part of the manager, pastor, leader, worker, and/or parishioner.

The research reported here suggests a corporate personality for a congregation can be identified. The initial question centered on whether the selection of membership at Redeemer Lutheran Church was a function of type. The uniqueness of this research is its focus on the corporate entity utilizing the MBTI with the membership to identify a corporate personality. Comparisons were then made between that corporate personality and a number of people who have left the group; become inactive.

Method

The study sample consisted of 127 participants who were administered the English version of Form G of the MBTI. Active confirmed members of Redeemer accounted for 76 of the MBTIs. Essentially, every active adult member participated; only members whose health had restricted their mental capabilities were excluded. Approximately 60 “inactive” members who still live in the area were personally contacted and invited to participate. Of these, 51 returned completed MBTIs.

Demographic information on the groups follows: Active members; males 29, females 47; 11 were in their late teens and twenties, 13 in their 30s, 17 in their 40s, 18 in their 50s 12 in their 60s, and 5 were 70 or older. One was Black and one Hispanic, with the remainder being Caucasian. Inactive members, all Caucasian; males 21, females 30; 3 were in their 20s, 5 in their 30s, 10 in their 40s 18 in their 50s, 11 in their 60s, and 4 were age 70 or older. The congregation is in an upper middle class neighborhood in a urban setting in northern California. Average education of the participants is approximately at a junior college level.

The MBTI scores were analyzed by CAPT and selection ratio tables developed. These tables compared each group to the other and to the standard CAPT sample of 9320 High School students from Pennsylvania. Unfortunately this research was conducted before the publication of the type distribution as reported by Hammer and Mitchell (1996). However, I believe the primary strength lies in the comparison of the members to the inactives.

In addition, a congregational inventory for identifying corporate personality was developed and administered to active members. This inventory was modeled after Gordon Lawrence’s (1979, 1982) work and adapted with language appropriate for corporate congregational use from the tables “Effects of Preferences in Work Situations” from Gifts Differing (Myers & Myers, 1980). This congregational inventory was developed prior to the publication of Bridges’ Organizational Character Index, (1992) and utilized situational language which was more reflective of the nature of congregations. The congregational inventory also asked respondents to indicate length of membership. Thirty-four valid congregational inventories were returned and considered. They represented a cross section of the congregation in terms of gender, age, and of membership under the tenure of the various pastors from the founding pastor to present. The hypothesis behind this congregational inventory was that through its use the members would identify a corporate personality type beyond each individual projecting his or her personality onto the group. The inventory is presented in the original study (Rehak, 1991).

Results

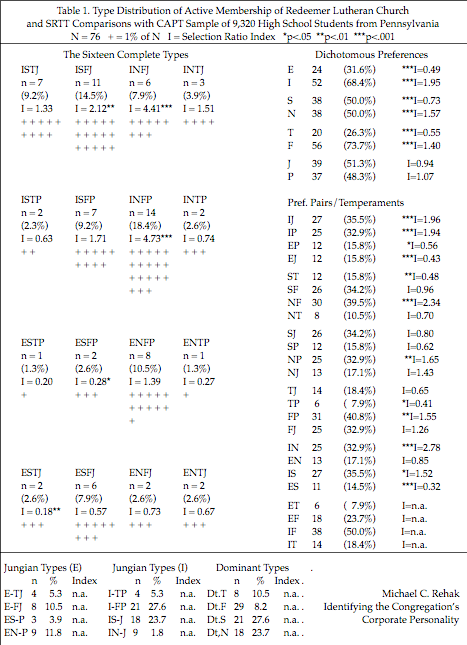

To some degree, membership has been a matter of self-selection by type. The selection ratios for ISTJ, ISFJ, INFJ, INTJ, ISFP, INFP, and ENFP were all greater than 1.00, as is evident from Table 1 and ISFJ (p< .01) and INFJ and INFP (p< .001) were significantly different from the comparison group from CAPT. Conversely, 9 of the 16 types had ratios less than 1.00, indicating an under-representation, with significance for the ESTJ (p< .01) and the ESFP (p< .05). Table 1 also shows levels of significance for attitude and function. Preferences I, N, and F (p< .001) displayed a greater than expected frequency, whereas E, S, and T (p< .001) were far less than in the general population. Reviewing the four combinations of functions without the attitude reveals the NF (p< .001) as the most prevalent, with almost 40%. STs (p< .01) were underrepresented.

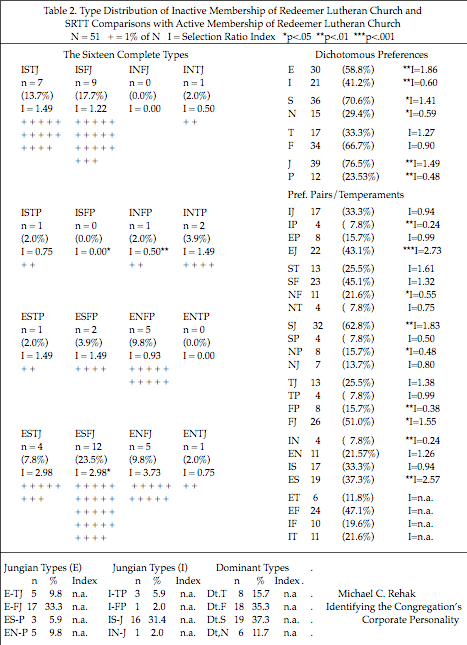

The sample of inactives was compared to the active group and the results are shown in Table 2. In the inactive group, there was a significant overrepresentation of ESFJ (p< .05) and an underrepresentation of ISFP (p< .05) and INFP (p< .01). The selection ratios for the individual preferences show significantly high ratios for E and J (p< .01) and S (p<.05). When the inactives were compared to the general population, levels of significance for overrepresentation were noted for the ESFJ and ENFJ (p< .05) and the ISFJ (p< .01) preferences.

On the congregational inventory, 41.2% of the respondents identified INFP as the corporate personality of the congregation. There was a notable absence of or low response for the ISTJ, ISFJ, INFJ, INTJ, ESFJ, ENFJ, and ENTJ corporate type. Although the INF preferences were clearly noted in the self-selection ratios, it was the perceiving attitude that was highlighted by the congregational inventory. The congregational inventory displayed only a 17.6% preference for the judging, attitude with the perceiving being 82.4% This compares to the MBTI composite of judging at 51.3% and perceiving 48.7%.

Discussion

The results provide statistical data suggesting that the membership of Redeemer Lutheran Church has been formed by a self-selection process. This congregation does have a corporate personality type: INFP. Comparing the active members to inactives further supports the theory.

Function with attitude may play a role in a person’s choice of whether to remain active or to become inactive. Although the judging function of feeling with an introverted attitude (IF) is preferred for the INFP, 76.5% of members who became inactive extravert the judging function from either the dominant or auxiliary position; F 51.0% and T 25.5%. Nearly half of the inactives (47.1%) were EFs, whereas 50% of the active members are IFs. This raises questions of the differences between people who extravert and people who introvert the judging function, and further, of what difference it makes in relationships when this is done from the dominant position as opposed to the auxiliary position.

The weakness of the congregational inventory is that it has not been validated. Validation is important if use in other congregations is considered. As with the MBTI membership scores, IF was the most prevalent choice in the congregational inventory. In the congregational inventory, EN is ranked second compared to the presence of IS as second in the composite membership. The EN in this case may be very important. Because of the congregation introverted quality, many members may not see or sense the dominant introverted feeling function of the corporate personality. Participants in the congregational inventory may be responding to what they experience in the operating, interactive side of congregational life. INFP types tend to respond to the outer world of people and things through the auxiliary function: the intuition with an attitude that is extraverted (EN). The primary activities of expression and communication, of leadership and visioning, and of interactive worship and programs would be exercised though the intuitive function using the extraverted attitude. As the length of membership and age of participants in the inventory increased they were more likely to see the congregation as extroverted.

The identification of INFP as the corporate personality in the congregational inventory was not a matter of simple projection. Only half of the INFPs participated in the congregational inventory. There were two ISTJs, four INFJs, one INTJ, and two ESFJs among the subjects who completed the congregational inventory and not a single inventory was returned which considered any of these four types as the corporate personality. Direct projection by individuals of their types to the corporate type did not occur in a significantly discernible pattern. Rather, people were able to identify a corporate personality for the congregation.

This study adds to the growing body of work in the area of corporate personality and specifically raises questions about why some people leave groups feeling they have not been heard, don’t fit in and are not appreciated, or simply just do not belong. The dynamics are greater and more subtle than simply “I never did get along with the boss,” or “The pastor doesn’t have time for me.”

Identification and acknowledgement of a corporate personality type has led this congregation into greater corporate health. This congregation, as a corporate entity, can now celebrate its giftedness. It approaches its weaker areas of ministry with patience and understanding. This has resulted in a decrease in the negative self-criticism. Previously, the congregation negatively compared itself to perceived national church or synodical expectations and to the ministries of other

congregations. This congregation, as with many others, readily knew what it was not, or, what it was expected to be, but rarely really knew what it was. A greater sense of corporate health was claimed when one of the leadership council observed, “Oh, all we need, then, is a few good extraverts to advertise we are the church for introverts.” Although this healing observation was not completely accurate, it was reflective of a humor centered in self-knowledge and acceptance. Such health can be enhanced through greater corporate awareness for any group of people who gather together for work or play.

I believe that the awareness of a corporate type helped open the congregation for internal scrutiny of its programs, communication patterns, and polity to see how these aspects of corporate life matched the strengths and limitations of its personality. This new information and perspective empowered the congregation to develop its own worship style apart from denominational form. Programs such as evangelism we reviewed under the guiding question, “How does this program reflect the nature and the personality of the congregation.” It became vitally important that programs designed to attract new members were congruent with and reflected the personality type of the congregation. This was seen as a matter of honesty. It was not meant to attract members of only one type. The reality is that all 16 types are represented in the membership of this congregation. The judgment was that it would help prospective members know more clearly the issues, values, and styles of the congregation. It is believed that this approach should reduce the false expectations of a number of those joining which leads to them becoming disillusioned and inactive.

The potential of this research will be embraced as corporate members and leaders are willing to look at their being together as having a life expression beyond themselves and that this life expression has a personality that guides and shapes activities, decisions, communications, and values. The greater part of wisdom then will be for us to look at various groupings of people-- congregations, corporations, staffs, or social organizations-- and see comparatively our differing gifts.

Reference

Bridges, W. (1992). The Character of Organizations. Palo Alto, California: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Harbaugh, G. L. (1988) God’s Gifted People. Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House.

Hammer, A. L. & Mitchell, W.D. (1996). The Distribution of MBTI Types In the US by Gender and Ethnic Group. Journal of Psychological Type, 37, 2-15.

Hirsh, S. K. & Kummerow, J. M. (1987). Introduction to Type in Organizations. Palo Alto, California: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Isachsen, O. & Berens, L. V. (1988). Working Together - A Personality Centered Approach to Management. San Juan Capistrano, California: Newworld Management Press.

Lawrence, G. (1979, 1982). People Types and Tiger Stripes. Gainesville, Florida: Center for Application of Type, Inc.

Myers, I. B., with P. B. Myers (1980). Gifts Differing. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Oswald, R. M. & Kroeger, O. (1988). Personality Type and Religious Leadership. Washington D.C.: The Alban Institute, Inc.

Rehak, M. C. (1991). Identifying The Congregation’s Corporate Personality. Doctoral Thesis, Graduate Theological Union Library, Berkeley, California.

Wink, W. (1986). Unmasking The Powers. Philadelphia: Fortress Press.

Yeakley, F. R., Jr. (1983). Implications of Communication Style Research for Psychological Type Theory. Journal of Psychological Type, 6, 2-13.